Annual Report 2021–22

Table of contents

- Message from the Chairperson

- Section 1–How did the Board do?

- The Board’s Performance

- Applications for Judicial Review

- Section 2–What is the Board?

- Composition

- Our Jurisdiction

- Section 3–What does the Board do?

- The Board’s Specific Responsibilities

- Section 4–Key Decisions

- Canada Industrial Relations Board

Encouraging Fair and Productive Workplaces

The Board focuses on helping employers, employees and the trade unions representing them resolve their disputes in a timely manner in order to minimize the potential negative impact of conflict in the workplace.

—Ginette Brazeau, Chairperson, Canada Industrial Relations Board

Message from the Chairperson

I am pleased to present the activities and results of the Canada Industrial Relations Board (the Board) for fiscal year 2021–22.

The Board’s workload has continued to increase since its mandate was expanded through the 2019 legislative amendments to the Canada Labour Code. The Board now handles quite a wide range of matters, including complex labour disputes between unions and federally regulated employers, complaints from self-represented employees challenging a disciplinary action or termination, and appeals of decisions made by the Labour Program of Employment and Social Development Canada regarding claims for unpaid wages and health and safety matters.

The Board’s task is to provide expert and timely intervention to resolve these matters. To achieve this objective, we not only decide matters but also help the parties resolve their disputes amicably without the need for lengthy litigation. A large proportion of cases filed with the Board are resolved through these dispute settlement efforts. For example, in fiscal year 2021–22:

- 92% of unjust dismissal complaints were settled at the mediation stage; and

- 44% of unfair labour practice complaints were resolved without the need for adjudication.

The Board encourages and promotes alternative dispute resolution mechanisms as an effective way of ensuring fair and practical results for all parties involved in these disputes. I am grateful to the Board’s designated officers, members, adjudicators and support staff, who work extremely hard to deliver these services. Their unmatched professionalism and dedication make it possible for the Board to successfully meet the challenges of the day.

This report provides details on the Board’s workload and the results achieved over the past fiscal year. I hope you will find it informative and helpful in understanding the Board’s work.

Section 1–How did the Board do?

The Board’s Performance

Volume of Matters

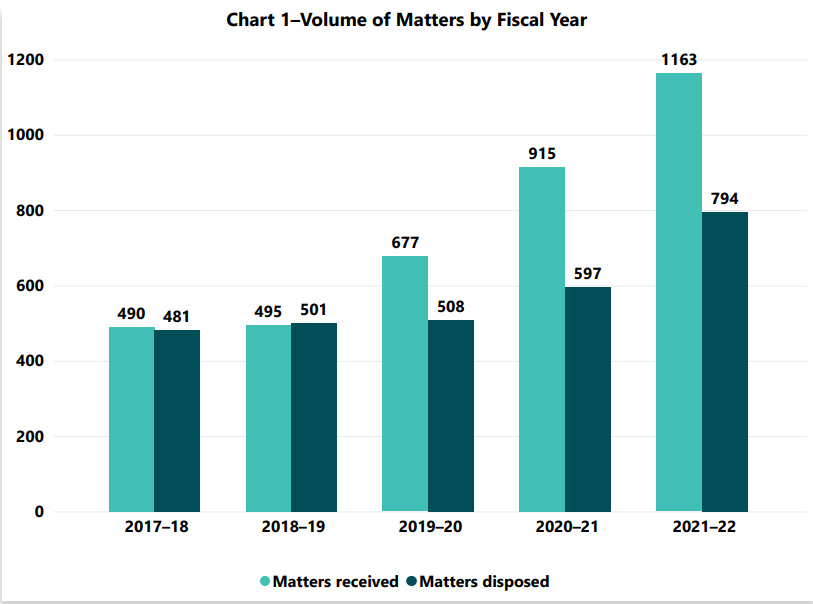

The Board’s expanded mandate under Parts II and III of the Canada Labour Code (the Code), which it obtained in 2019, has had a direct impact on its workload. In fiscal year 2021–22, the number of matters filed with the Board increased by 27% over the previous year, which also represents an increase of over 134% compared to pre-2019–20 levels.

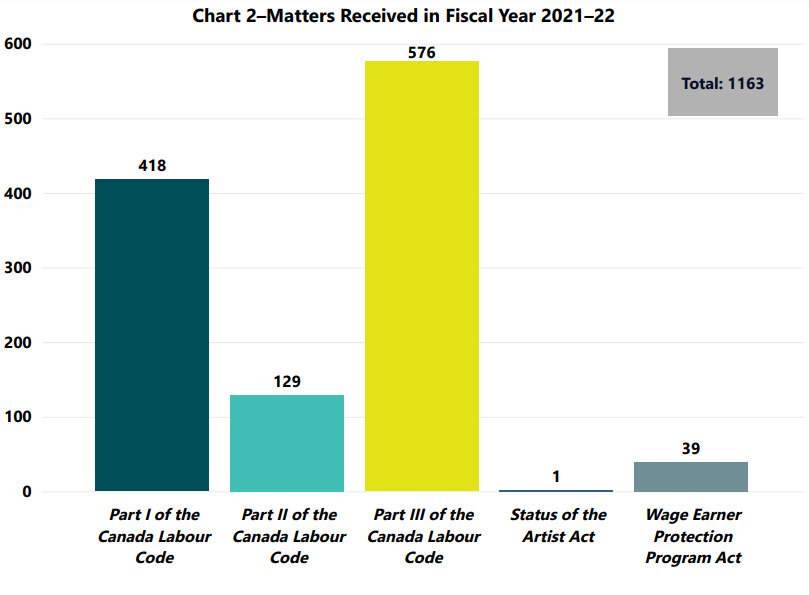

The Board received a total of 1,163 applications and complaints in the 2021–22 fiscal year. Of these matters, 544 were unjust dismissal complaints and wage recovery appeals filed under Part III of the Code, representing 47% of all matters received during the year. Under Part II of the Code, the Board received 129 applications and complaints, including reprisal complaints and applications to appeal decisions issued by the Head of Compliance and Enforcement of Employment and Social Development Canada (the Head). Matters under Part II of the Code represented 11% of the Board’s incoming caseload. The number of matters under Part I of the Code increased to 418 compared to 380 in the previous fiscal year and represented 36% of the Board’s incoming caseload.

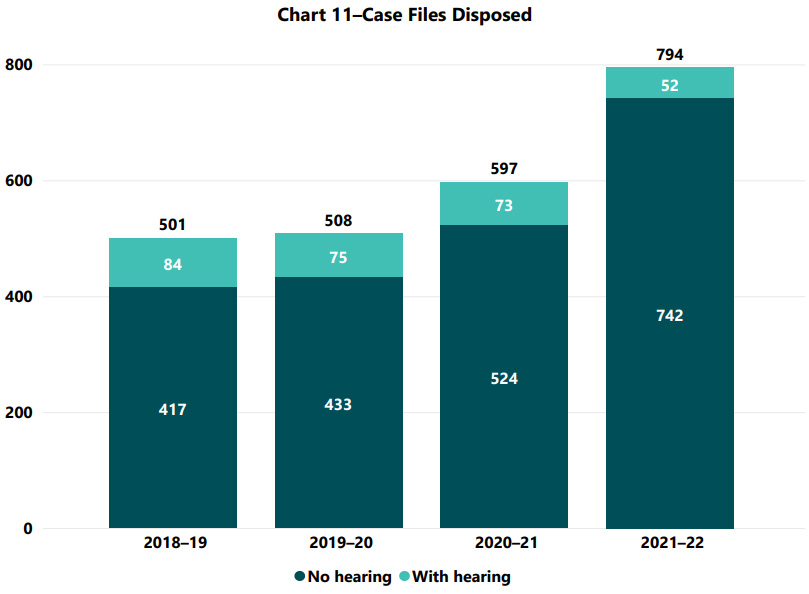

The number of cases that the Board disposed of in fiscal year 2021–22 continued to increase over the previous year at 794 matters closed. The pending caseload has increased to 1,186 matters.

Chart 1–Volume of Matters by Fiscal Year–Text version

| 2017–18 | 2018–19 | 2019–20 | 2020–21 | 2021–22 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Matters received | 490 | 495 | 677 | 915 | 1163 |

| Matters disposed | 481 | 501 | 508 | 597 | 794 |

* Please note that the data in this annual report may differ slightly from the data communicated in previous annual reports as a result of the adjustment of information in the Board's case management system.

Chart 2–Matters Received in Fiscal Year 2021–22–Text version

| Total: 1163 | |

|---|---|

| Part I of the Canada Labour Code | 418 |

| Part II of the Canada Labour Code | 129 |

| Part III of the Canada Labour Code | 576 |

| Status of the Artist Act | 1 |

| Wage Earner Protection Program Act | 39 |

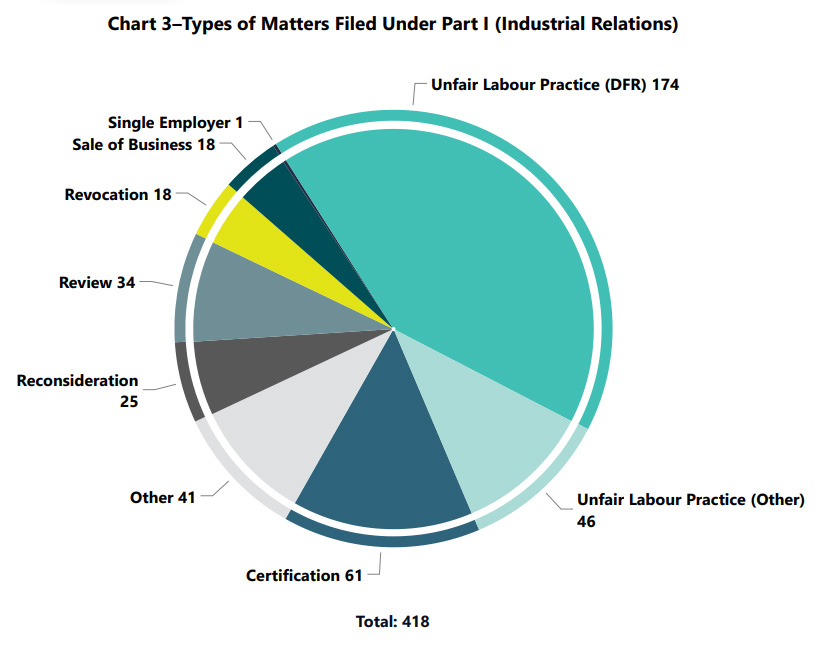

Chart 3–Types of Matters Filed Under Part I (Industrial Relations)–Text version

| Total 418 | |

|---|---|

| Unfair Labour Practice (DFR) | 174 |

| Unfair Labour Practice (Other) | 46 |

| Certification | 61 |

| Other | 41 |

| Reconsideration | 25 |

| Review | 34 |

| Revocation | 18 |

| Sale of Business | 18 |

| Single Employer | 1 |

Part I of the Code (Industrial Relations)

Unfair Labour Practice

Unfair labour practice (ULP) complaints, which include duty of fair representation (DFR) complaints, represent the largest number of cases filed under Part I of the Code. The Board spends a lot of effort in helping the parties in those cases find a resolution. In fiscal year 2021–22, 44% of ULP complaints were resolved without the need for adjudication.

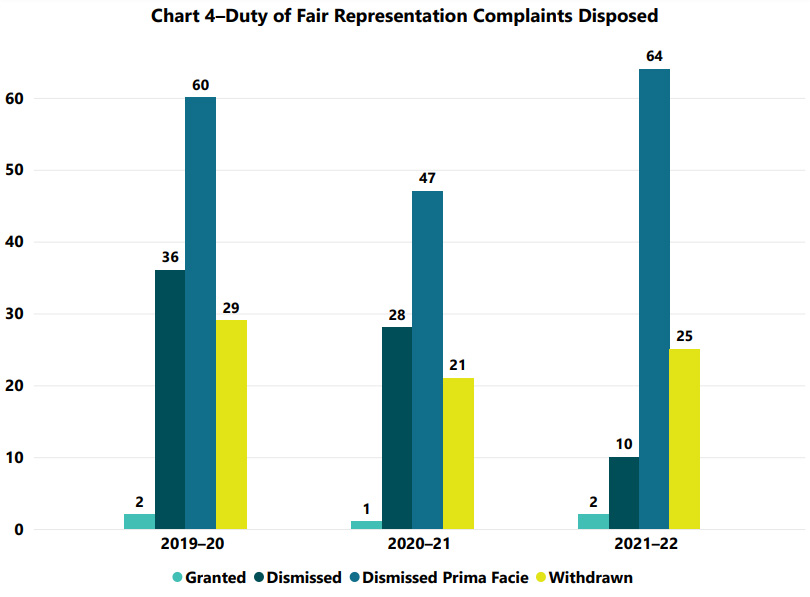

DFR complaints represent the largest component of ULP complaints. The number of DFR complaints that were filed increased greatly this year to 174 compared to 87 cases last year. This increase was mostly due to issues arising from the implementation of vaccination policies in various workplaces. In addition to offering dispute settlement options to the parties in these matters, the Board disposed of approximately two thirds of these complaints through a preliminary assessment of the complaints (which is called a prima facie case analysis). This process allows the Board to triage the DFR complaints it receives and respond to them as efficiently as possible.

Chart 4–Duty of Fair Representation Complaints Disposed–Text version

| 2019–20 | 2020–21 | 2021–22 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Granted | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Dismissed | 36 | 28 | 10 |

| Dismissed Prima Facie | 60 | 47 | 64 |

| Withdrawn | 29 | 21 | 25 |

* Please note that, in last year's report, the figures regarding the decisions that were dismissed or dismissed prima facie were reversed. The issue has been resolved in the present report following a verification of data.

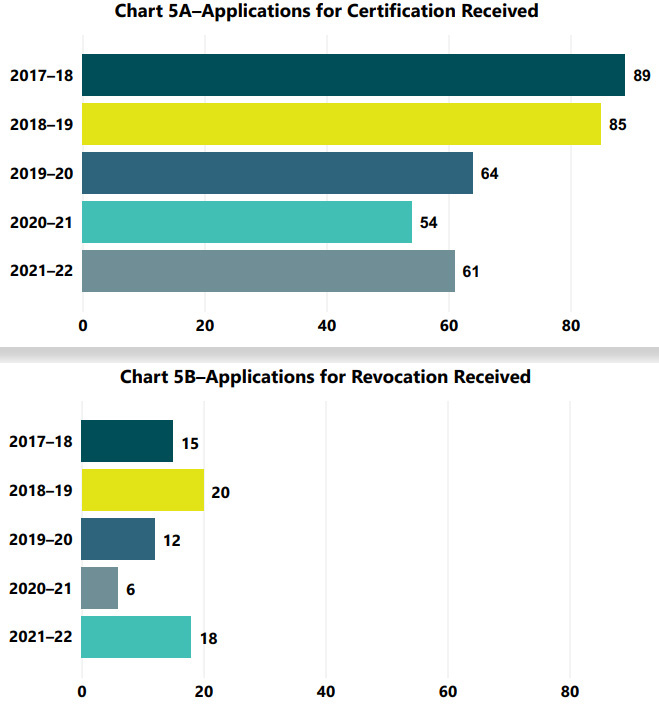

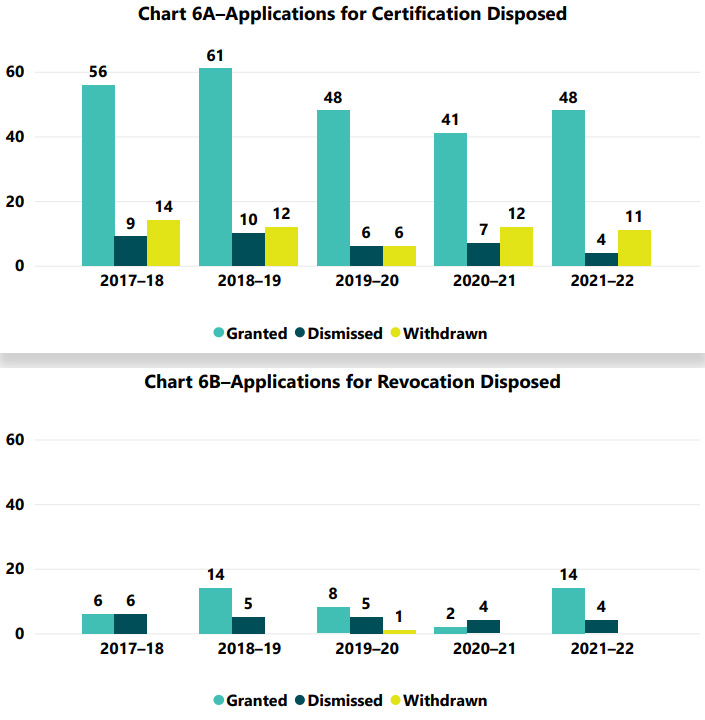

Applications for Certification and Revocation

Applications for certification also represent a large portion of incoming matters under Part I of the Code. In fiscal year 2020–21, the number of applications for certification had dropped to 54 compared to 64 in the previous year and 85 in the year prior to that. In fiscal year 2021–22, the number of applications for certification received went up slightly to 61. As for the applications for certification that the Board disposed of during fiscal year 2021–22, 76% were granted, 6% were dismissed and 18% were withdrawn. The number of applications for revocation received also increased to 18 compared to 6 in the previous year. As for the applications for revocation that the Board disposed of during fiscal year 2021–22, 78% were granted and 22% were dismissed.

Chart 5A, 5B-Applications for Certification and Revocation Received -Text version

| Total 353 | |

|---|---|

| 2017–18 | 89 |

| 2018–19 | 85 |

| 2019–20 | 64 |

| 2020–21 | 54 |

| 2021–22 | 61 |

| Total 71 | |

|---|---|

| 2017–18 | 15 |

| 2018–19 | 20 |

| 2019–20 | 12 |

| 2020–21 | 6 |

| 2021–22 | 18 |

Chart 6A, 6B –Applications for Certification Disposed–Text version

| 2017–18 | 2018–19 | 2019–20 | 2020–21 | 2021–22 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Granted | 56 | 61 | 48 | 41 | 48 |

| Dismissed | 9 | 10 | 6 | 7 | 4 |

| Withdrawn | 14 | 12 | 6 | 12 | 11 |

| 2017–18 | 2018–19 | 2019–20 | 2020–21 | 2021–22 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Granted | 6 | 14 | 8 | 2 | 14 |

| Dismissed | 6 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 |

| Withdrawn | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

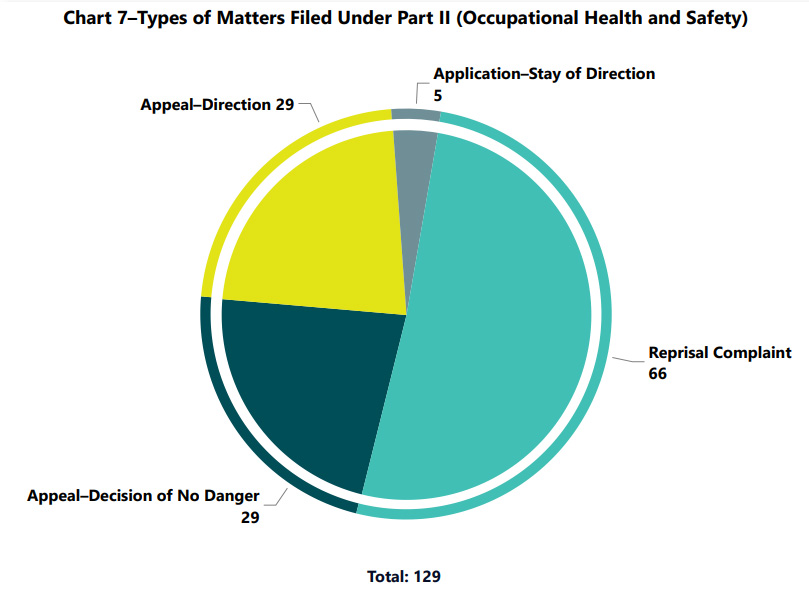

Part II of the Code (Occupational Health and Safety)

A total of 129 matters under Part II of the Code were received in fiscal year 2021–22, an increase over the previous year. Reprisal complaints represent just over 50% of all matters under Part II, while applications to appeal a decision of no danger represent 23%, applications to appeal a direction issued by the Head represent 23%, and applications for a stay of a direction represent 4%.

Chart 7–Types of Matters Filed Under Part II (Occupational Health and Safety)–Text version

| Total: 129 | |

|---|---|

| Application–Stay of Direction | 5 |

| Reprisal Complaint | 66 |

| Appeal–Decision of No Danger | 29 |

| Appeal–Direction | 29 |

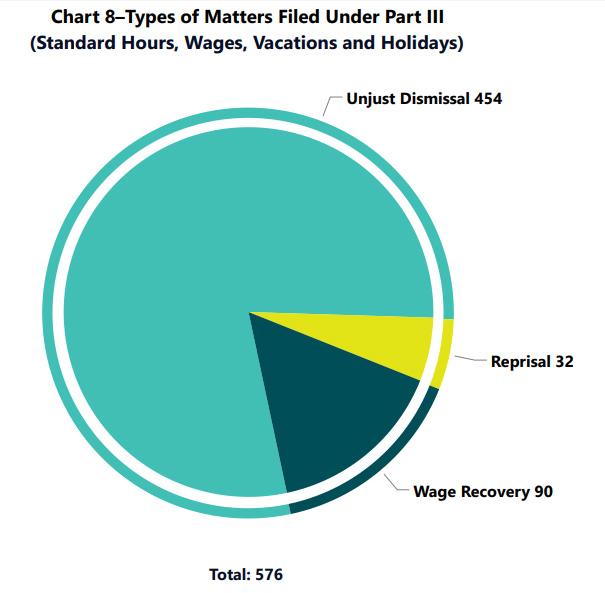

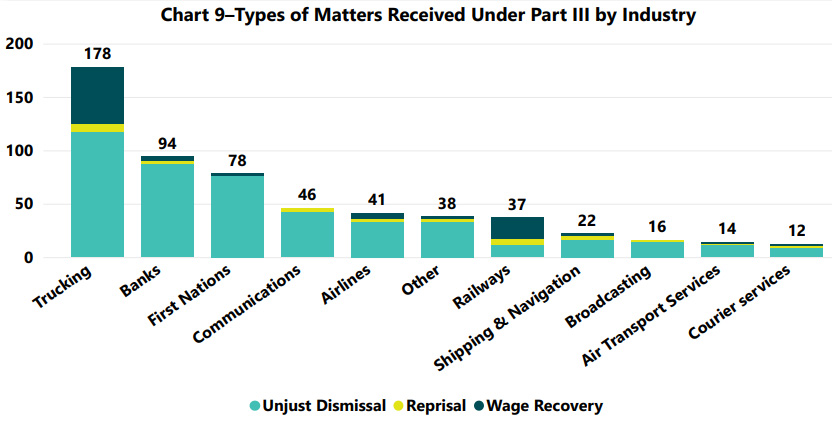

Part III of the Code (Standard Hours, Wages, Vacations and Holidays)

Matters under Part III of the Code represented 50% of all matters that the Board received during the 2021–22 fiscal year, or 576 cases. The majority of these cases were unjust dismissal complaints, representing 79% of the caseload under Part III.

As the number of matters filed under Part III of the Code represents the largest proportion of the Board’s caseload, it is of interest to note that these matters overwhelmingly involve three particular sectors: trucking, banking and First Nations undertakings.

Chart 8–Types of Matters Filed Under Part III (Standard Hours, Wages, Vacations and Holidays)–Text version

| Total: 576 | |

|---|---|

| Unjust Dismissal | 454 |

| Reprisal | 32 |

| Wage Recovery | 90 |

Chart 9–Types of Matters Received Under Part III by Industry–Text version

| Trucking | Banks | First Nations | Communications | Airlines | Other | Railways | Shipping & Navigation | Broadcasting | Air Transport Services | Courier services | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unjust Dismissal | 117 | 88 | 76 | 43 | 33 | 33 | 12 | 16 | 15 | 12 | 9 |

| Reprisal | 8 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Wage Recovery | 53 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 5 | 2 | 20 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 178 | 94 | 78 | 46 | 41 | 38 | 37 | 22 | 16 | 14 | 12 |

* The “Other” category includes, among other industries, Crown corporations, feed mills and grain elevators, nuclear power and passenger charter services and buses.

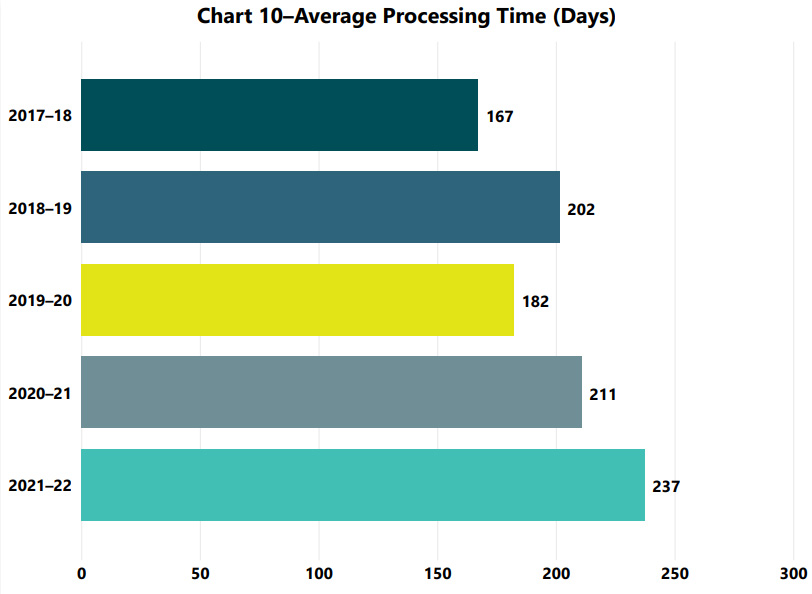

Processing Times

In fiscal year 2021–22, the Board’s case files were processed, on average, within 237 days, or about seven months. This includes all the steps involved in processing a matter, such as gathering the written submissions of the parties, offering mediation, holding an oral hearing if necessary and issuing a written decision. This is an increase over the previous year as the Board continues to adjust to its new and diverse mandates.

Chart 10–Average Processing Time (Days)–Text version

| Total 999 | |

|---|---|

| 2017–18 | 167 |

| 2018–19 | 202 |

| 2019–20 | 182 |

| 2020–21 | 211 |

| 2021–22 | 237 |

Decision-Making

The Board strives to provide timely and legally sound decisions that are consistent across similar matters in order to establish reliable and clear jurisprudence. The Board issues detailed reasons for decision in matters of broader national significance and precedential importance. For other matters, the Board issues concise letter decisions, which speeds up the decision-making process and brings more expedient solutions to the parties in labour relations matters. The Board also disposes of certain matters by issuing an order that summarizes its decision. One part of the overall processing time is the time required by a Board panel to prepare and issue a decision after hearing a matter.

A panel may decide a case without an oral hearing based on the written and documentary evidence on file, such as investigation reports and written submissions. In fact, most cases are decided or disposed of without an oral hearing. In some cases, the Board may schedule an oral hearing to obtain further evidence and arguments in order to decide the matter. Whether the Board holds a hearing, as well as the length of the hearing, will affect the overall processing time.

Section 14.2(2) of the Code states that a panel must render its decision and give notice of it to the parties within 90 days after the day on which it reserved its decision or within any further period that may be determined by the Chairperson. The average decision making time during the 2021–22 fiscal year was 98 days. The Board remains committed to improving its rate of disposition to ensure that it does not allow a backlog of cases to occur.

Chart 11–Case Files Disposed–Text version

| 2018–19 | 2019–20 | 2020–21 | 2021–22 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No hearing | 417 | 433 | 524 | 742 |

| With hearing | 84 | 75 | 73 | 52 |

| Total | 501 | 508 | 597 | 794 |

Applications for Judicial Review

Another indicator of the Board’s performance, as well as an indicator of the quality and soundness of its decisions, is the number of applications for judicial review of Board decisions and the percentage of decisions upheld after these reviews. In this regard, the Board continues to perform very well.

During the 2021–22 fiscal year, ten applications for judicial review of Board decisions were filed with the Federal Court of Appeal (FCA). As of March 31, 2022, three of these applications were withdrawn and the remaining seven were ongoing. In total, the FCA disposed of 11 applications for judicial review of Board decisions over the course of the fiscal year, with four being dismissed and seven being withdrawn.

The Federal Court Trial Division received four applications for judicial review of Board decisions during the 2021–22 fiscal year. As of March 31, 2022, one of these applications was withdrawn, one was dismissed, one was referred to the FCA and one was ongoing. In addition, one application before the Federal Court, which was filed before fiscal year 2021–22, was withdrawn.

During the 2021–22 Fiscal Year

The Board issued 221 letter decisions, 205 orders and 49 Reasons for decision.

44% of unfair labour practice complaints were settled without requiring a decision by the Board.

6 certifications were renewed under the Status of the Artist Act.

Section 2–What is the Board?

Composition

The Canada Labour Code (the Code) provides for the Canada Industrial Relations Board (CIRB or the Board) to be composed of:

- one full-time neutral Chairperson;

- two or more full-time neutral Vice-Chairpersons; and

- a maximum of six full-time Members representing employers and employees in equal numbers.

Part-time Vice-Chairpersons and Members may also be appointed to the CIRB. The Chairperson and Vice-Chairpersons of the CIRB must have experience and expertise in labour relations.

At the end of the fiscal year, the Board was composed of the following appointees:

Chairperson:

Ginette Brazeau was first appointed as Chairperson on December 28, 2014, after previously serving as Executive Director and General Counsel with the CIRB. Ms. Brazeau’s current term expires on December 27, 2024.

5 full-time Vice-Chairpersons:

Annie G. Berthiaume, term ending January 25, 2025

Louise Fecteau, term ending November 30, 2025

Sylvie M.D. Guilbert, term ending July 1, 2024

Roland A. Hackl, term ending July 1, 2024

Allison Smith, term ending January 4, 2025

3 part-time Vice-Chairpersons:

Paul Love, term ending November 30, 2025

Lynne Poirier, term ending November 28, 2025

Jennifer Webster, term ending June 30, 2024

4 employer representative Members:

Richard Brabander, term ending December 20, 2023 (full-time Member)

Vacant (full-time Member)

Elizabeth Cameron, term ending January 3, 2024 (full-time Member)

Barbara Mittleman, term ending December 20, 2023 (part-time Member)

4 employee representative Members:

Lisa Addario, term ending June 24, 2024 (full-time Member)

Gaétan Ménard, term ending February 25, 2024 (full-time Member)

Daniel Thimineur, term ending May 10, 2024 (full-time Member)

Paul Moist, term ending December 20, 2023 (part-time Member)

The Code allows members whose terms expire to complete the duties that were assigned to them during their active terms (section 12(2)).

The Chairperson can also appoint external adjudicators to determine matters under Part II, III or IV of the Code. A list of qualified adjudicators is established by the Chairperson after consultation with the Client Consultation Committee.

Visit the Board’s Web site to access the list of current Board members and their backgrounds.

Our Jurisdiction

Overall Mandate:

The CIRB is an independent, representational and quasi-judicial tribunal. Its mandate is to contribute to, and promote, a harmonious industrial relations climate in the federally regulated sector. It also ensures that federal workplaces comply with health and safety legislation and minimum employment standards.

The CIRB is responsible for interpreting and administering Part I (Industrial Relations) and certain sections of Part II (Occupational Health and Safety), Part III (Standard Hours, Wages, Vacations and Holidays) and Part IV (Administrative Monetary Penalties) of the Code.

The CIRB is also responsible for interpreting and administering Part II (Professional Relations) of the Status of the Artist Act and dealing with appeals under the Wage Earner Protection Program Act.

Sectors or Industries that Fall Under the Board’s Jurisdiction:

The CIRB has jurisdiction in all provinces and territories with respect to federal works, undertakings or businesses. These normally include the following sectors:

- Broadcasting (radio and television)

- Chartered banks

- Postal services

- Airports and air transportation

- Marine shipping and navigation

- Canals, pipelines, tunnels and bridges (crossing provincial borders)

- Railways and road transportation that involves the crossing of a provincial or international border

- Telecommunications

- Grain handling and uranium mining and processing

- Most public and private sector activities in Yukon, Nunavut and the Northwest Territories

- Some First Nations undertakings

- Federal Crown corporations (for example, the national museums)

This jurisdiction covers about 910,000 employees and their employers (18,000) and includes businesses that have a major economic, social and cultural impact on Canadians from coast to coast.

The variety of activities that take place in the federally regulated private sector, as well as the geographical scope and national significance of this sector, contribute to the uniqueness of the federal jurisdiction and the Board’s role.

Part II of the Code (Occupational Health and Safety):

Aside from the sectors described above, the Board also has jurisdiction over the federal public service to decide applications to appeal certain decisions and directions made by the Head of Compliance and Enforcement of Employment and Social Development Canada (the Head). Specifically, when the Head makes a decision about a refusal to perform dangerous work or issues a direction under health and safety legislation, the decision or direction can be appealed to the Board.

The federal public service represents about 320,000 employees and the various federal government departments and separate employers.

Status of the Artist Act:

The Board is also responsible for interpreting and administering Part II (Professional Relations) of the Status of the Artist Act, which, in addition to broadcasters and Crown corporations, applies to federal government departments and agencies.

Wage Earner Protection Program Act:

The Wage Earner Protection Program provides for the payment of eligible wages owing to workers whose employer is insolvent. Service Canada processes the claims made under this program.

The Board decides all applications to appeal the final decisions made by the Minister of Labour (or the delegate) under the Wage Earner Protection Program Act, regardless of whether the former employer was provincially or federally regulated for labour and employment purposes.

Section 3–What does the Board do?

The Canada Industrial Relations Board (CIRB or the Board) plays an important role in recognizing and protecting the rights of employees, unions and employers. In accordance with the policy set out in the Canada Labour Code (the Code), the Board promotes the well-being of Canadian workers, unions and employers through the encouragement of free collective bargaining and the constructive settlement of disputes.

The Board’s Specific Responsibilities

Part I of the Code (Industrial Relations)

The CIRB is responsible for interpreting and applying Part I of the Code. The Board performs several activities under this part, since complaints and applications may raise various labour relations questions that need to be addressed.

Specifically, the Board may:

- determine employer/employee status;

- define bargaining units that are appropriate for collective bargaining;

- grant, modify or terminate collective bargaining rights;

- investigate, mediate and decide unfair labour practice complaints;

- issue cease and desist orders in cases of unlawful strikes and lockouts;

- determine whether the work of certain employers falls under federal jurisdiction;

- deal with the complex labour relations issues that come with corporate mergers and acquisitions; and

- determine the level of services that need to be maintained during a legal work stoppage to prevent an immediate and serious danger to the safety or health of the public.

The Board engages in these activities with a firm commitment to process, hear and determine matters fairly, quickly and efficiently. Before adjudication, the Board actively works with the parties to help them settle their disputes through mediation or alternative dispute resolution.

Part II of the Code (Occupational Health and Safety)

The CIRB is also responsible for determining certain matters under Part II of the Code. Under this part, the Board hears and determines reprisal complaints where employees may claim that they were disciplined or terminated because they exercised their health and safety rights. The Board is also responsible for hearing and deciding applications to appeal decisions made by the Head of Compliance and Enforcement of Employment and Social Development Canada (the Head) related to work refusals or directions issued by the Head to employers.

More specifically, in the case of a work refusal, an employee may challenge before the Board one of the following decisions by the Head:

- that a danger does not exist;

- that a danger exists, but the danger is a normal condition of employment; or

- that a danger exists, but the refusal puts the life, health or safety of another person directly in danger.

An employer, an employee or a trade union that disagrees with a direction issued by the Head can challenge that direction by filing an application to appeal with the Board. These are statutory appeals, meaning that the Board will review each case with any new evidence or information that will be available and provided by the parties to the appeal.

Part III of the Code (Standard Hours, Wages, Vacations and Holidays)

Under Part III of the Code, the Board is responsible for mediating and deciding:

- unjust dismissal complaints from employees who are not represented by a union;

- wage recovery appeals where an employer or an employee disagrees with a decision or a payment order issued by the Head; and

- reprisal complaints where an employee believes that their employer retaliated against them for exercising their rights under employment standards legislation.

Part IV of the Code (Administrative Monetary Penalties)

Part IV of the Code came into force on January 1, 2021. Under this part, the CIRB is responsible for determining appeals of administrative monetary penalties imposed by the Head against federally regulated employers.

Other

The CIRB is also responsible for professional relations between self-employed artists and producers at federally regulated broadcasters, federal government departments and agencies and Crown corporations, under the Status of the Artist Act. This includes defining the sectors of cultural activity suitable for collective bargaining and certifying artists’ associations in these sectors.

The Board also decides applications to appeal decisions made by the Minister of Labour (the Minister) under the Wage Earner Protection Program Act. In these cases, the Board reviews the written documents on file to determine whether there was an error of law or jurisdiction in the Minister’s decision.

Outreach

The Board supports the collective efforts of workplace partners in developing good relationships and pursuing constructive dispute resolution practices. As a representative Board composed of members representing employers and unions in equal numbers, the Board prioritizes proactive engagement with the labour relation community by taking part in various outreach activities. These activities:

- allow the Board and its designated officers to inform the community of the Board’s policies and procedures;

- provide opportunities to learn about the needs of employers, workers and the union organizations that represent them;

- ensure the Board remains relevant to the parties it serves; and

- enhance the parties’ ability to participate in the Board’s processes.

The Board also plays an important role in international organizations that support government agencies responsible for promoting dispute resolution based on the shared interests of the parties and harmonious labour relations. The CIRB’s active participation in the Association of Labor Relations Agencies and the International Forum of Labour and Employment Dispute Resolution Agencies allows for a broader discussion on the new challenges and dynamics arising in modern workplaces. These forums also provide the Board with invaluable access to best practices that it can use to improve its performance, maximize the use of its resources and increase the impact of its services.

The CIRB’s Client Consultation Committee

The Board maintains a dialogue with its clients through the Client Consultation Committee (the Committee) to strengthen relationships and gather feedback from its client communities. The Committee provides advice and recommendations to the Board’s Chairperson on how the Board can best meet its mandate and its clients’ needs.

The Committee is made up of representatives chosen by the Board’s major client groups, including:

- Federally Regulated Employers in Transportation and Communication (FETCO);

- Canadian Labour Congress (CLC);

- Unifor;

- Confédération des syndicats nationaux (CSN);

- Canadian Association of Labour Lawyers (CALL) (representing counsel for the trade unions); and

- Canadian Association of Counsel to Employers (CACE) (representing counsel for the employers).

The Committee meets three times a year to discuss Board performance and any new initiatives that will affect the processing of matters and increase the impact of its services.

Section 4–Key Decisions

Canada Industrial Relations Board

WestJet, an Alberta Partnership, 2021 CIRB 985

In support of its application for certification filed pursuant to section 24(1) of the Canada Labour Code (the Code), Unifor (the union) filed electronic membership evidence in the form of either scanned paper cards or electronic cards. WestJet, an Alberta Partnership (the employer) raised several issues regarding the application, including concerns over the validity of the electronic membership evidence filed by the union.

The Board reiterated that membership evidence must be accurate and reliable. It stated that section 31 of the Canada Industrial Relations Board Regulations, 2012 (the Regulations), does not exclusively set out what evidence would satisfy the requirements of section 28 of the Code and that nothing in the Code or the Regulations precludes the filing of electronic evidence. The Board determined that the provisions of the Code dealing with membership evidence are broad enough to allow electronic membership evidence, provided that the Board can assess the evidence filed with the application. It stated that the acceptance of electronic membership evidence is the logical next step for the federal labour relations community. The Board concluded that it would accept electronic membership evidence where it could ascertain the reliability of the system used and verify the evidence through rigorous audit trails.

The Board was satisfied, in this matter, that the method used to collect the electronic membership cards, including digital payment of the initiation fee, was reliable and verifiable and could be relied upon as a true expression of employee wishes.

Watson, 2022 CIRB 1002

This decision dealt with the duty of fair representation (DFR) owed by the Canadian Union of Public Employees (the union) to its members in response to a mandatory vaccination policy unilaterally implemented by Air Canada (the employer). The policy was implemented following the federal government’s stated intention to issue an order that would direct all airlines (as well as other employers) to adopt and implement a mandatory vaccination policy for their employees, providing for limited exemptions due to a certified medical contraindication or religious grounds.

Essentially, the employer’s policy stated that employees who were not fully vaccinated by a certain date would be suspended without pay for a period of six months. Ms. Watson (the complainant), a flight attendant, was one of a group of employees who requested that the union pursue a policy grievance in response to this policy. The union refused to do so. The complainant’s main allegation was that the union’s decision not to pursue a policy grievance was arbitrary and thus breached the DFR. The complainant alleged that the union had not sufficiently considered the prejudicial impact of the policy on those bargaining unit members who would not comply with the policy due to medical or other personal reasons.

The Board dismissed the complaint. In its decision, the Board noted that the union had sought two legal opinions and put the question of whether to pursue a policy grievance to the executive committee. The Board reiterated that there is no absolute right or obligation to pursue a particular grievance to arbitration. A union must often choose between the competing interests of its members but, when doing so, must consider all of the interests and do so fairly.

The Board was of the view that the union had done so in this case, having turned its mind to the issue and taken the necessary steps to evaluate its chances of successfully challenging the policy. The Board also stated that the union supported vaccination generally as an effective way to ensure the health and safety of its members. This position, although in opposition to certain members’ views, was not in and of itself a breach of the DFR.

An application for judicial review of this decision is pending in the Federal Court of Appeal.

Rusnak, 2021 CIRB 999

In this decision, the Board clarified its jurisdiction over health and safety reprisal complaints (Part II of the Canada Labour Code) filed by persons employed in the federal public service and the types of decisions Registrars can make in processing such complaints.

Ms. Rusnak applied for reconsideration of the Registrar’s letter refusing to process her health and safety reprisal complaint (section 133(1)).

The Board explained that the applicable legislation provides that for persons employed in the federal public service, it only has jurisdiction over applications to appeal directions issued by ministerial delegates (now officials delegated by the Head of Compliance and Enforcement) and decisions of no danger.

The Federal Public Sector Labour Relations and Employment Board has jurisdiction over health and safety reprisal complaints filed by persons employed in the federal public service. Given that Ms. Rusnak’s employer was a federal government department (Global Affairs Canada), the Board did not have jurisdiction to deal with her health and safety reprisal complaint.

The Board determined that, in the interest of expediency, the Registrar may make straightforward decisions on jurisdiction in processing a complaint or application, when it is plain and obvious from the facts presented therein.

Cook, 2021 CIRB 995

In this decision, the Board determined that when employees are eligible to file a complaint under the unjust dismissal regime, they are not eligible to file a wage recovery complaint for termination pay (section 230) and/or severance pay (section 235) under the Canada Labour Code (the Code).

In this case, Ms. Cook had worked for the Canadian Pacific Railway Company (the employer) for 33 years and filed a wage recovery complaint for termination and severance pay, alleging that she had been constructively dismissed. This complaint was assigned to an inspector of Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC), who issued a notice of unfounded complaint. Ms. Cook then filed a request for review of the inspector’s decision with the ESDC, and the Minister of Labour referred the request for review to the Board to be treated as an appeal.

The employer raised an objection to the Board’s jurisdiction to deal with the matter on the basis that Ms. Cook was eligible to file an unjust dismissal complaint but had not done so. The employer’s argument was mainly based on statements made by the Supreme Court of Canada (SCC) in Wilson v. Atomic Energy of Canada Ltd., 2016 SCC 29; [2016] 1 S.C.R. 770 (Wilson), regarding the purpose of the unjust dismissal provisions.

The Head of Compliance and Enforcement for the Minister of Labour provided submissions indicating that they did not agree with the employer’s argument and that employees should be able to choose the process they would like in order to address the termination of their employment.

Essentially, the Board based its decision on the different purposes and legislative intent behind the severance and termination provisions and the unjust dismissal provisions. The Board noted that in Wilson, the SCC had confirmed that the unjust dismissal provisions were intended to displace the minimum standards set out at sections 230 and 235 of the Code and provide greater rights and protections. As such, the Board found that sections 230 and 235 only apply to circumstances that fall outside the scope of the unjust dismissal provisions and are not an alternative to them.

Lennox, 2021 CIRB 1009

Mr. Lennox (the complainant) filed an unjust dismissal complaint alleging that he had been constructively dismissed by 882819 Ontario Limited, o/a Morrice Transportation (the employer).

He argued that the employer had changed the terms and conditions of his employment by considering him a part-time instead of a full-time driver. He also argued that a series of incidents, including alleged harassment, had caused him to resign.

The Board dismissed the complaint. In cases involving constructive dismissal, it is the complainant who bears the burden of proof. The Board observed that the Federal Court of Appeal had confirmed that the unjust dismissal provisions set out in the Canada Labour Code cover constructive dismissal. The Board relied on the test set out in Potter v. New Brunswick Legal Aid Services Commission, 2015 SCC 10; [2015] 1 S.C.R. 500. In particular, constructive dismissal can be established in two ways.

The first way involves a two-step analysis to assess whether there has been a substantial breach of the employment contract. First, the decision-maker must objectively determine whether the employer’s unilateral change is a breach (express or implied). Second, if the change constitutes a breach, the decision-maker must assess whether a reasonable person in the same situation as the employee would have felt, at the time the breach occurred, that an essential term of the employment contract was being substantially changed.

The second way involves a series of acts that show that the employer no longer intended to be bound by the employment contract. The decision-maker must consider the cumulative effect of the employer’s past actions and determine whether they demonstrate that the employer intended to no longer be bound by the employment contract.

The Board held that, when assessed objectively, the employer’s statements and actions did not indicate that it had breached a term of the complainant’s employment. There was no evidence to demonstrate that the employer had made a substantial change to the employment contract.

Additionally, the Board was not satisfied that the series of events relied on by the complainant demonstrated that the employer no longer intended to be bound by the employment contract.