Annual Report 2019–20

Table of contents

Encouraging Fair and Productive Workplaces

"The Board focuses on helping employers, employees and the trade unions representing them resolve their disputes in a timely manner in order to minimize the potential negative impact of conflict in the workplace."

—Ginette Brazeau, Chairperson, Canada Industrial Relations Board

Message from the Chairperson

I am pleased to present to Parliament and to Canadians a report on the annual performance of the Canada Industrial Relations Board (the CIRB or the Board) for the fiscal year ending March 31, 2020.

The past few years have been marked by continuous change for the Board. Fiscal year 2019–20 was no different, as the Board took on new responsibilities under Part II (Occupational Health and Safety) and Part III (Standard Hours, Wages, Vacations and Holidays) of the Canada Labour Code and under the Wage Earner Protection Program Act. These new mandates represent an important expansion in the Board’s areas of expertise and a significant increase in its caseload. Throughout the year, efforts were focused on putting in place the procedures and policies necessary to respond to the new types of cases while maintaining or improving our response rate on all applications and complaints filed with the Board. In addition, and in support of the Board’s efforts to respond to the increased workload, the Governor-in-Council renewed the appointment of two Vice Chairpersons and appointed three additional Vice-Chairpersons to the Board. These are welcomed appointments that provide stability and predictability in the adjudicative resources of the Board for the next five years.

As this report will show, average processing times of complaints and applications have improved over the previous fiscal year. However, it is also apparent with the increasing workload that there is more to be done to ensure the Board is able to respond in a timely way to those who require its assistance. This will remain the focus of our work going forward.

The Board is also preparing its transition to a new case management system. Significant effort and resources have been directed to the completion of the work necessary to deploy a new system that will enable the Board to leverage modern technology to support its case management practices. The enhanced technology tools will allow for improved access to and use of electronic files, e-communications and performance reporting.

The Board’s objective through this period of change and transition has been focused on helping employers, employees and the trade unions representing them resolve their disputes in a timely manner in order to minimize the potential negative impact of conflict in the workplace. The Board works extremely hard to meet the needs and expectations of the labour relations community, and my colleagues are to be commended for their engagement and dedication. As a team, we are truly committed to building positive working relationships in federally regulated workplaces.

Section 1–What is the Board?

Composition

The Canada Labour Code (the Code) provides for the Canada Industrial Relations Board (the CIRB or the Board) to be composed of one full-time neutral Chairperson, two or more full-time neutral Vice-Chairpersons and not more than six full-time Members representing employers and employees in equal numbers. Part-time Vice-Chairpersons and Members may also be appointed to the CIRB. The Chairperson and Vice-Chairpersons of the CIRB must have experience and expertise in labour relations.

At the end of the fiscal year, the Board was composed of the following appointees:

Chairperson:

Ginette Brazeau was first appointed as Chairperson on December 28, 2014, after previously serving as Executive Director and General Counsel with the CIRB. Ms. Brazeau’s current term expires on December 27, 2024.

5 full-time Vice-Chairpersons:

Annie G. Berthiaume, term ending January 25, 2025

Louise Fecteau, term ending November 30, 2025

Sylvie M.D. Guilbert, term ending July 1, 2024

Roland A. Hackl, term ending July 1, 2024

Allison Smith, term ending January 4, 2025

3 part-time Vice-Chairpersons:

Paul Love, term ending November 30, 2025

Lynne Poirier, term ending November 28, 2025

Jennifer Webster, term ending June 30, 2024

4 employer representative Members:

Richard Brabander, term ending December 20, 2023 (full-time Member)

Thomas Brady, term ending May 28, 2021 (full-time Member)

Barbara Mittleman, term ending December 20, 2023 (part-time Member)

Vacant (full-time Member)

4 employee representative Members:

Lisa Addario, term ending June 24, 2024 (full-time Member)

Gaétan Ménard, term ending February 25, 2024 (full-time Member)

Daniel Thimineur, term ending May 10, 2024 (full-time Member)

Paul Moist, term ending December 20, 2023 (part-time Member)

In accordance with section 12(2) of the Code, members whose terms expire may continue to complete the duties assigned to them during their active terms.

In addition, the Chairperson has the statutory authority to appoint external adjudicators to determine matters under Parts II, III or IV of the Code. A list of qualified adjudicators is established by the Chairperson after consultation with the Client Consultation Committee and can be viewed on the Board’s Official website.

Visit the Board’s Official website to access the list of current Board members and their backgrounds

Our Jurisdiction

Overall Mandate:

The CIRB is an independent, representational, quasi-judicial tribunal responsible for the interpretation and administration of Part I (Industrial Relations) and certain provisions of Part II (Occupational Health and Safety), Part III (Standard Hours, Wages, Vacations and Holidays) and, as of January 1, 2021, Part IV (Administrative Monetary Penalties) of the Code. The CIRB is also responsible for the interpretation and administration of Part II (Professional Relations) of the Status of the Artist Act and the adjudication of appeals under the Wage Earner Protection Program Act.

The Board’s mandate is to contribute to, and promote, a harmonious industrial relations climate in the federally regulated sector while also ensuring compliance with health and safety legislation and adherence to minimum employment standards in federal workplaces.

Sectors or Industries that Fall Under the Board’s Jurisdiction:

The CIRB has jurisdiction in all provinces and territories with respect to federal works, undertakings or businesses. These normally include the following sectors:

- Broadcasting (radio and television)

- Chartered banks

- Postal services

- Airports and air transportation

- Marine shipping and navigation

- Canals, pipelines, tunnels and bridges (crossing provincial borders)

- Railways and road transportation that involve the crossing of a provincial or international border

- Telecommunications

- Grain handling and uranium mining and processing

- Most public and private sector activities in Yukon, Nunavut and the Northwest Territories

- Some First Nations undertakings

- Federal Crown corporations (for example, the national museums)

This jurisdiction covers some 900,000 employees and their employers (12,000), and it includes enterprises that have a significant economic, social and cultural impact on Canadians from coast to coast. The variety of activities conducted in the federally regulated private sector, as well as its geographical scope and national significance, contribute to the uniqueness of the federal jurisdiction and the role of the CIRB.

Part II of the Code (Occupational Health and Safety):

In addition to the sectors described above, the Board also has jurisdiction over the federal public service for the purpose of adjudicating applications to appeal decisions made by the Head of Compliance and Enforcement of Employment and Social Development Canada (the Head) concerning refusals to perform dangerous work and directions issued by the Head under the health and safety legislation.

The federal public service represents some 250,000 employees and the various federal government departments and separate employers.

Status of the Artist Act:

The Board is also responsible for the interpretation and administration of Part II (Professional Relations) of the Status of the Artist Act, which, in addition to broadcasters and Crown corporations, applies to federal government departments and agencies.

Section 2–What does the Board do?

The Canada Industrial Relations Board (the CIRB or the Board) fulfills a vital role in recognizing and protecting the rights of employees, trade unions and employers. In accordance with the policy set forth in the Canada Labour Code (the Code), the Board promotes the well-being of Canadian workers, trade unions and employers through the encouragement of free collective bargaining and the constructive settlement of disputes.

The Board’s Specific Responsibilities

Part I of the Code (Industrial Relations)

The CIRB is responsible for the interpretation and application of the provisions of Part I (Industrial Relations) of the Code. The Board undertakes a number of activities under this jurisdiction, as complaints or applications may raise a number of labour relations questions that must be addressed.

More specifically, the Board may:

- determine employer/employee status;

- define bargaining units that are appropriate for collective bargaining;

- grant, modify or terminate collective bargaining rights;

- investigate, mediate and adjudicate complaints of unfair labour practice;

- issue cease and desist orders in cases of unlawful strikes and lockouts;

- determine whether the work of certain employers falls within the federal areas of constitutional jurisdiction;

- deal with the complex labour relations implications of corporate mergers and acquisitions; and

- determine the level of services that must be maintained during a legal work stoppage to prevent an immediate and serious danger to the safety or health of the public.

The Board engages in these activities with a firm commitment to process, hear and determine matters fairly, expeditiously and economically. Before adjudication, the Board actively works to help parties resolve their disputes through mediation or alternative dispute resolution.

Part II of the Code (Occupational Health and Safety)

The CIRB is also responsible for determining certain matters under Part II (Occupational Health and Safety) of the Code. Under this mandate, the Board hears and determines complaints of reprisals where employees may claim that they were disciplined or terminated because they exercised their rights under the health and safety regime. Additionally, as of July 29, 2019, the Board is responsible for hearing and deciding applications to appeal decisions issued by the Minister related to work refusals or directions issued by the Minister to employers.

More specifically, in the context of a work refusal, an employee may challenge before the Board one of the following decisions issued by the Minister:

- that a danger does not exist;

- that a danger exists, but the danger is a normal condition of employment; or

- that a danger exists, but the refusal puts the life, health or safety of another person directly in danger.

In addition, an employer, an employee or a trade union that disagrees with a direction issued by the Minister can challenge that direction by filing an application to appeal with the Board.

These are statutory appeals, meaning that the Board will assess each case with any new evidence or information that will be available and presented by the parties to the appeal.

Part III of the Code (Standard Hours, Wages, Vacations and Holidays)

As part of its new expanded mandate, the Board is responsible for mediating and adjudicating the following:

- unjust dismissal complaints from employees who are not represented by a trade union;

- wage recovery appeals where an employer or an employee disagrees with a decision or a payment order issued by an inspector; and

- reprisal complaints where an employee believes that their employer retaliated against them for exercising their rights under employment standards legislation.

Other

The CIRB is also responsible for professional relations between self-employed artists and producers at federally regulated broadcasters, federal government departments and agencies and Crown corporations, pursuant to the Status of the Artist Act. This includes defining the sectors of cultural activity suitable for collective bargaining and certifying artists’ associations in these sectors.

As of July 29, 2019, the Board is now responsible for adjudicating applications to appeal decisions made by the Minister under the Wage Earner Protection Program Act. These matters involve a review of the written record to determine whether there was an error of law or an error of jurisdiction in the Minister’s decision.

Outreach

The Board supports the collective efforts of trade unions and employer organizations to develop good relations and pursue constructive dispute resolution practices. As such, the Board actively participates in outreach activities, both nationally and internationally. These outreach efforts allow the Board to learn about the needs of employers, workers and the union organizations that represent them as well as develop and maintain exemplary practices in its service delivery. Some of the Board’s outreach activities are further described here.

The CIRB’s Client Consultation Committee

The Board maintains dialogue with its clients through the Client Consultation Committee (the Committee) to strengthen linkages and obtain feedback from its client communities. The Committee provides advice and recommendations to the Board’s Chairperson on ways in which the Board can best meet its mandate and the needs of its clients.

The Committee is composed of representatives selected by the Board’s major client groups, including:

- Federally Regulated Employers in Transportation and Communication (FETCO);

- Canadian Labour Congress (CLC);

- Confédération des syndicats nationaux (CSN);

- Canadian Association of Labour Lawyers (CALL) (representing counsel for the trade unions); and

- Canadian Association of Counsel to Employers (CACE) (representing counsel for the employers).

The Committee convened three times during the 2019–20 fiscal year. The discussions continued to focus on Board performance and also centred on the implementation of legislative changes which assigned new areas of responsibility to the Board. In particular, the Committee provided guidance and advice to the Chairperson on the selection of external adjudicators who can be appointed to determine complaints of unjust dismissal and wage recovery appeals.

National Industrial Relations Conference

The Board again partnered with the Federal Mediation and Conciliation Service in holding another successful National Industrial Relations Conference in September 2019. The Conference offers a unique program which brings together representatives from labour and management from across Canada to discuss key issues of the day. The topics presented at the Conference focused on the future of work and the shifts that are already redefining the workplace. The Conference also showcased success stories of union management partnerships.

The Conference attracted over 200 delegates from all sectors of the federal jurisdiction. Its success speaks to the dynamic nature of industrial relations in the federal sector and the benefit of maintaining these forums to allow employer and union representatives to forge relationships and build on them to encourage productive and harmonious workplaces.

Other National and International Forums

The Board participates in the Laskin Moot Court Competition and the National Labour Arbitration Competition, which both provide labour law students with practical learning opportunities.

The Chairperson of the Board and other Board members and officers also engage in outreach activities on the national and international level.

The Chairperson participates in the annual meeting of chairpersons of labour relations boards in Canada. This meeting provides an opportunity to take stock of the realities in which all labour relations boards in Canada operate and identify trends across the country in order to prepare and implement mechanisms to better react and respond to the needs of the parties that appear before the Board.

The Board also plays a leading role in international organizations whose objective is to support government agencies responsible for promoting dispute resolution based on the shared interests of the parties and harmonious labour relations. The CIRB’s active participation in the Association of Labor Relations Agencies and the International Forum of Labour and Employment Dispute Resolution Agencies allows for broader dialogue on the new challenges and dynamics arising in modern workplaces. These forums also provide the Board with invaluable access to best practices that it can emulate and adopt to improve its performance, maximize the use of its resources and increase the impact of its services.

Section 3–How did the Board do?

The Board's Performance

Number of calls for information received through the Board’s 1-800 line in 2019–20: 2482 calls compared to 1584 the previous year.

Volume of Matters

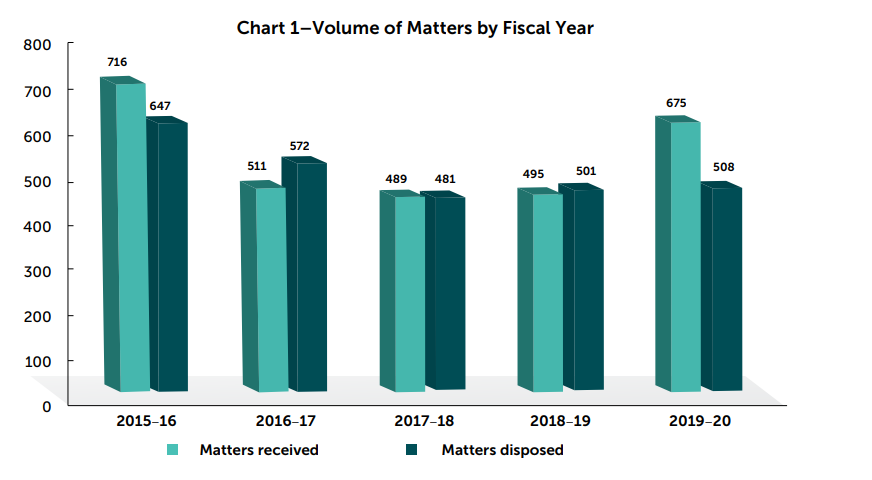

The nature of the demand for services provided by the Canada Industrial Relations Board (the Board) varies from year to year based on various factors, such as the economy. The number of applications and complaints received in the last year increased significantly over the previous years. An increase of 36% in the caseload is largely attributable to the new mandates that were transferred to the Board as of July 29, 2019. A total of 675 applications and complaints were received in the 2019–20 fiscal year. Of these, 121 matters were unjust dismissal complaints or wage recovery appeals filed under Part III of the Canada Labour Code (the Code), representing 18% of all matters received during the year. Under Part II of the Code, the Board received 22 applications to appeal decisions issued by the Minister. When adding the complaints of employer reprisals, the total of matters under Part II of the Code represents 10.7% of the Board's incoming caseload.

The number of cases disposed of by the Board in the last year remained consistent with the previous year at 508 matters closed. Consequently, the pending caseload has increased considerably with the new mandates and is expected to increase further into the next fiscal year.

Chart 1–Volume of Matters by Fiscal Year Text version

| 2015–16 | 2016–17 | 2017–18 | 2018–19 | 2019–20 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Matters received | 716 | 511 | 489 | 495 | 675 |

| Matters disposed | 647 | 572 | 481 | 501 | 508 |

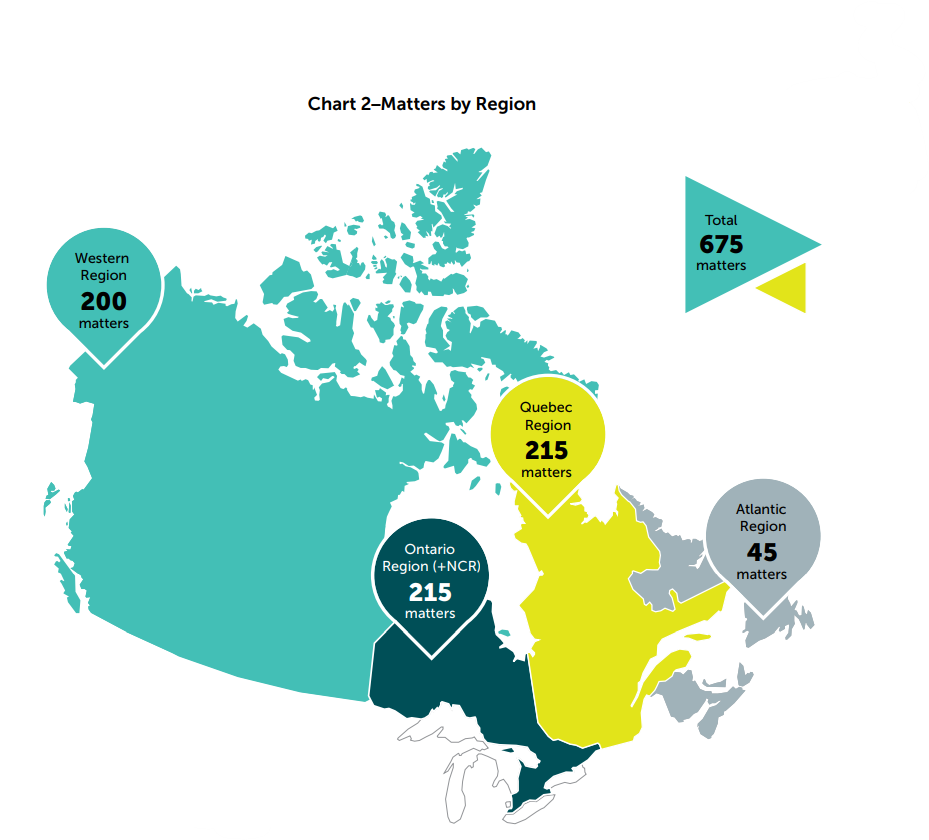

Number of Incoming Matters by Region

The Board’s regional offices in Vancouver (British Columbia), Toronto and the National Capital Region (Ontario), Montréal (Quebec) and Dartmouth (Nova Scotia) shared the workload as illustrated in the chart below.

Chart 2–Matters by Region Text version

| Western Region | Ontario Region (+NCR) | Quebec Region | Atlantic Region | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total 675 matters | 200 matters | 215 matters | 215 matters | 45 matters |

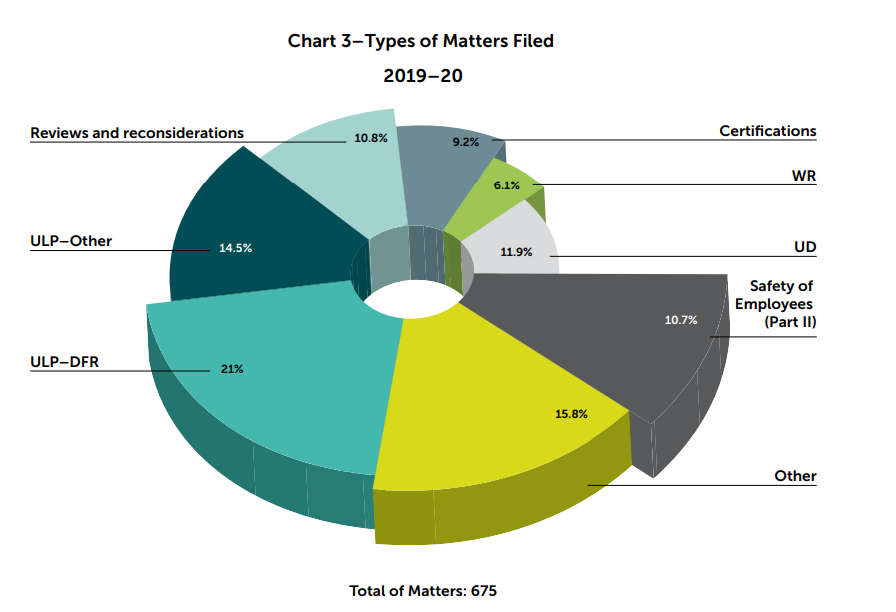

Chart 3–Types of Matters Filed Text version

| Total of Matters: 675 | 2019–20 |

|---|---|

| Certifications | 9.2% |

| WR | 6.1% |

| UD | 11.9% |

| Safety of Employees (Part II) | 10.7% |

| Other | 15.8% |

| ULP–DFR | 21% |

| ULP–Other | 14.5% |

| Reviews and reconsiderations | 10.8% |

Unfair Labour Practice

Unfair labour practice (ULP) complaints, including duty of fair representation (DFR) complaints, represent the largest number of cases filed under Part I of the Code. The Board spends considerable effort in providing assistance to the parties in those cases in support of their efforts to find a resolution. In 2019–20, 42% of ULP complaints were resolved without the need for adjudication.

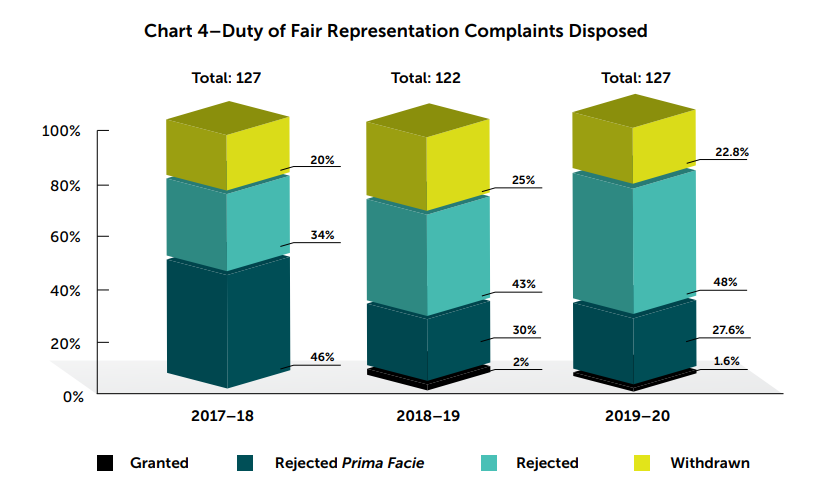

DFR complaints represent the largest component of ULP complaints. The number of DFR complaints increased this year to 142 cases compared to 116 cases last year. In addition to offering dispute settlement options to the parties in these matters, the Board also disposes of approximately one third of these complaints through a preliminary assessment of the complaints (which is called a prima facie case analysis). This allows the Board to triage the complaints and respond to them in the most efficient manner.

Chart 4–Duty of Fair Representation Complaints Disposed Text version

| 2017–18 | 2018–19 | 2019–20 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Granted | 0% | 2% | 1.6% |

| Rejected Prima Facie | 46% | 30% | 27.6% |

| Rejected | 34% | 43% | 48% |

| Withdrawn | 20% | 25% | 22.8% |

| Total | 127 | 122 | 127 |

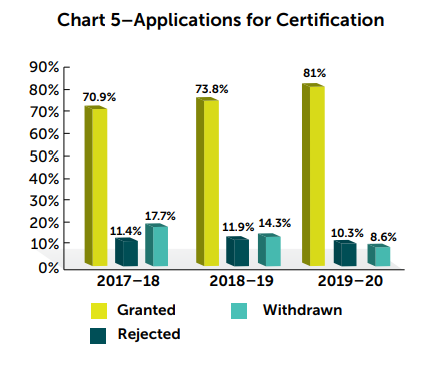

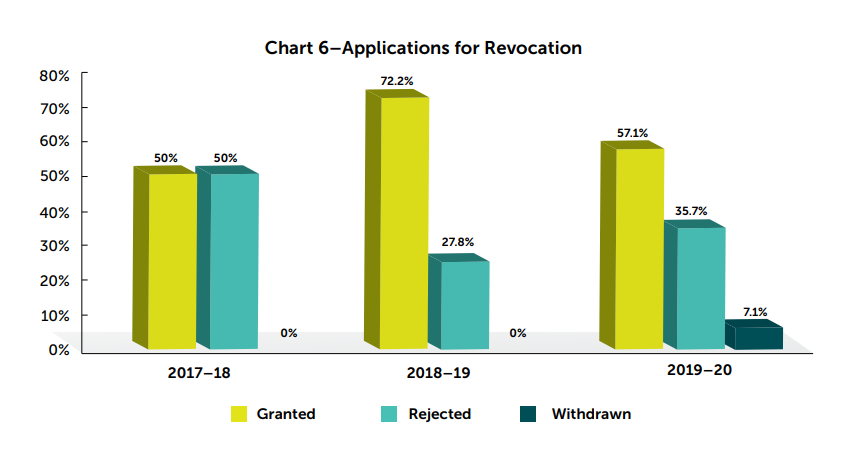

Applications for Certification and Revocation

Applications for certification also represent a significant portion of incoming matters under Part I of the Code. However, in 2019–20, the number of applications for certification dropped to 64 compared to 85 in the previous year. The percentage of these applications that were granted increased from 74.7% in 2018–19 to 81% this fiscal year. The number of applications for revocation also dropped to 13 compared to 21 the previous year. The percentage of applications for revocation that were granted decreased from 73.7% to 57.1% over the same period.

Chart 5–Applications for Certification Text version

| 2017–18 | 2018–19 | 2019–20 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Granted | 70.9% | 73.8% | 81% |

| Rejected | 11.4% | 11.9% | 10.3% |

| Withdrawn | 17.7% | 14.3% | 8.6% |

Chart 6–Applications for Revocation Text version

| 2017–18 | 2018–19 | 2019–20 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Granted | 50% | 72.2% | 57.1% |

| Rejected | 50% | 27.8% | 35.7% |

| Withdrawn | 0% | 0% | 7.1% |

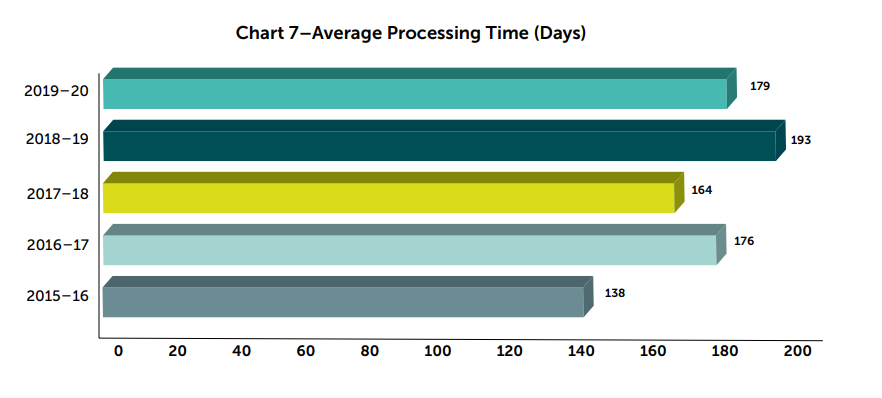

Processing Times

In 2019–20, the Board’s case files were processed, on average, within 179 days, or approximately six months. This includes all steps in the processing of matters, such as gathering the written submissions of the parties, offering mediation, holding an oral hearing if necessary and rendering a written decision. This is an improvement over the previous year. However, it remains above the processing times in previous years when the number of incoming matters was lower.

Chart 7–Average Processing Time (Days) Text version

| 2015–16 | 2016–17 | 2017–18 | 2018–19 | 2019–20 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 138 | 176 | 164 | 193 | 179 |

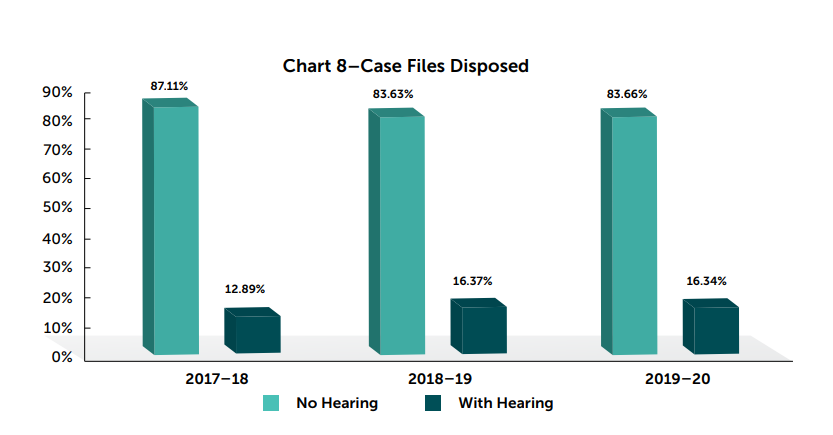

Decision-Making

The Board strives to provide timely and legally sound decisions that are consistent across similar matters in order to establish reliable and clear jurisprudence. The Board issues detailed reasons for decision in matters of broader national significance and precedential importance. For other matters, the Board issues concise letter decisions, which accelerates the decision-making process and brings more expedient solutions to the parties in labour relations matters.

The Board also disposes of certain matters by issuing an order that summarizes its decision. One component of the overall processing time is the length of time required by a Board panel to prepare and issue a decision following the completion of the hearing of a matter. A panel may decide a case without an oral hearing on the basis of the written and documentary evidence on file, such as investigation reports and written submissions, or it may schedule an oral hearing to obtain further evidence and arguments in order to decide the matter. Whether a hearing is held, as well as the length of the hearing, will impact the overall processing time.

During the 2019–20 Fiscal Year

The Board issued 191 letter decisions, 173 orders and 21 Reasons for decision.

42% of unfair labour practice complaints were settled without requiring a decision by the Board.

2 certifications were renewed under the Status of the Artist Act.

Chart 8–Case Files Disposed Text version

| 2017–18 | 2018–19 | 2019–20 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No Hearing | 87.11% | 83.63% | 83.66% |

| With Hearing | 12.89% | 16.37% | 16.34% |

Section 14.2(2) of the Code stipulates that a panel must render its decision and give notice of it to the parties within 90 days after the day on which it reserved its decision or within any further period that may be determined by the Chairperson. The Board met this objective, as the average decision-making time during the 2019–20 fiscal year was 87 days. The Board continues to demonstrate commitment and resolve in maintaining its rate of disposition to ensure that it does not allow a backlog of cases to occur.

Applications for Judicial Review

Another measure of the Board’s performance, as well as a measure of quality and soundness of its decisions, is the frequency of applications for judicial review of Board decisions and the percentage of decisions upheld as a result of these reviews. In this respect, the Board continues to perform very well.

During the 2019–20 fiscal year, thirteen applications for judicial review were filed with the Federal Court of Appeal. Three applications were dismissed while the other matters were pending before the court at the end of the fiscal year.

During that same period, two applications for judicial review were filed with the Federal Court.

Section 4–Changes and Challenges Moving Forward

New Mandates and External Adjudicators

Since the coming into force of new provisions of the Canada Labour Code (the Code) in July 2019, complaints and applications to appeal that are filed with the Canada Industrial Relations Board (the Board) under Part II and Part III of the Code are first assigned to officers of the Board, who work with the parties to attempt to reach a settlement. This is consistent with the Board’s established practice and procedures with respect to its existing mandate.

When the Board must adjudicate a complaint of unjust dismissal or an application to appeal a wage recovery matter or a direction related to health and safety, the Chairperson may assign a Vice-Chairperson of the Board to this task or, if necessary, an external adjudicator. An external adjudicator appointed by the Chairperson has all the powers, duties and functions conferred on the Board by the Code with respect to any matter to which the adjudicator has been appointed, and their orders, decisions and directions are deemed to be orders or decisions made or directions issued by the Board.

During the 2019–20 fiscal year, the majority of these new files were either resolved through mediation with the Board’s officers or determined by a Vice-Chairperson of the Board. However, as the number of matters continues to increase, additional adjudicative resources will be necessary.

In the fall of 2019, the Board announced a process on its website through which it sought to establish a list of qualified, experienced, impartial and dynamic external adjudicators with credibility in the Canadian labour relations community who could be appointed to hear these matters. The objective was to identify a small group of adjudicators from different regions who would bring diverse backgrounds and a broad range of experience and expertise to the Board.

The Chairperson conducted interviews and continues to do so as needed on the basis of the applications that were submitted as part of this process. The Board’s Client Consultation Committee was also invited to provide input on the selection criteria and on the list of proposed candidates. This work will continue into the next fiscal year in order to ensure that the Board has the necessary adjudicative resources to address the increased workload.

New Technology

Efforts are ongoing with the Board’s Secretariat to develop and implement a new case management system that will leverage modern technologies and enhance our ability to communicate electronically. These new electronic tools will allow us to offer online filing as well as a one-stop shop where users of the Board’s services will be able to share case-related documents and information. It is also expected that the new case management system will allow us to streamline some of our business processes and find efficiencies in the way we work.

The transition to a modern and technologically advanced operating environment is anticipated during fiscal year 2020–21. As with any transition, this will represent a significant change for Board members and staff and for users. Over the coming months, and as we move through these changes, focused efforts will be invested in training and communication to ensure that the new environment and process is well understood.

Virtual Hearings

At the end of the 2019–20 fiscal year, the onset of the global pandemic related to COVID-19 had an immediate impact on the Board’s operations. The Board’s offices across the country were closed, and employees and members of the Board were quickly able to work remotely and continue to provide services and process matters as required. In-person hearings had to be cancelled, and many matters were suspended for a period of time. The Board quickly explored alternative options and was able to offer virtual hearings and meetings using the Zoom platform. The Board will continue to hold hearings, pre-hearing conferences, meetings and mediations via teleconference or videoconference for the foreseeable future.

The Board also continues, as per its established practice, to dispose of a significant number of applications and complaints based solely on the written submissions of the parties without the need to hold an oral hearing. This has allowed the Board to continue to maintain its rate of disposition and process matters without undue delay.

There is no doubt that the challenges presented by the global pandemic have triggered a discussion with respect to new ways of working and reflections on innovative ways of adjudicating and resolving disputes.

Section 5–Key Decisions

Canada Industrial Relations Board

Duty of Employer Representative

Parrish & Heimbecker, Limited, 2019 CIRB 915

Parrish & Heimbecker, Limited (P&H), as a member employer, filed an application with the Board pursuant to section 34(6) of the Canada Labour Code (the Code) against its employer representative, the Maritime Employers Association (MEA). P&H alleged that the MEA had breached its duty of fair representation (DFR) when it had established a practice (the 2:40 Practice) with the International Longshoremen’s Association (ILA), in contravention of the labour requirements and break provisions of the collective agreement. P&H further alleged that because of the application of the 2:40 Practice, an accident involving an ILA employee had occurred on one of its vessels, causing significant damage.

Based on the pleadings in this case, the Board identified five specific issues to be determined: (1) whether the MEA had acted arbitrarily and in bad faith because it knew about the 2:40 Practice violations of the collective agreement and had failed to stop them; (2) whether the MEA had acted arbitrarily and in bad faith by refusing to pursue a grievance on behalf of P&H pertaining to the July 1, 2018, spout accident; (3) whether the MEA had engaged in discriminatory conduct as the 2:40 Practice only applies to member employers engaged in the grain industry; (4) whether the MEA had behaved arbitrarily in its investigation of the July 1, 2018, spout accident; and (5) whether the MEA had engaged in bad faith conduct in recent collective bargaining as a direct result of hostility and animosity toward P&H.

In order to resolve these issues, the Board had to first determine the scope of its jurisdiction and the nature of an employer representative’s DFR towards its members pursuant to section 34(6) of the Code. To this end, the Board reviewed its limited case law on section 34(6) as well as more general principles established in its section 37 case law.

The Board found that its limited case law pertaining to section 34(6) has consistently noted that an employer representative’s DFR under section 34(6) is similar to a union’s DFR under section 37 of the Code. As is the case in a section 37 DFR complaint against a union, the Board’s role in evaluating a DFR complaint of a member employer against an employer representative is to review the employer representative’s process in its handling of its members’ concerns. The Board’s role is not to assess the correctness of the employer representative’s decision or to act as an appeal body of that decision. Therefore, a member employer may only complain that an employer representative’s conduct in the discharge of its duties and responsibilities was arbitrary, discriminatory or in bad faith toward it. Having acknowledged these similarities, the Board then pointed out important differences between sections 37 and 34(6). Specifically, the Board noted that the scope of the DFR in sections 37 and 34(6) is not identical. While section 37 speaks specifically of “rights under the collective agreement,” section 34(6) speaks of “the discharge of the duties and responsibilities of an employer under this Part.” Having thus outlined the scope of section 34(6) and the distinctions to be made with section 37 complaints, the Board applied these notions to the issues to be determined.

With respect to the first issue raised, the Board was unable to find that the MEA had acted arbitrarily or in bad faith by agreeing to and continuing to apply the 2:40 Practice that it had previously negotiated with the ILA. In assessing the applicability of a union’s DFR in the context of amending collective agreements or agreeing to change terms and conditions of employment that are outside of the collective agreement, the Board has held that, provided that the union’s conduct in the process is free of arbitrary, discriminatory and/ or bad faith conduct, a union and an employer are not precluded from either modifying terms of a collective agreement during its term or agreeing to provisions beyond its scope. The Board noted that there was no reason why this same principle could not be applied to an employer representative chosen under section 34 in the longshoring industry. The Board then concluded that P&H had not presented any evidence that the MEA, in continuing to apply the 2:40 Practice that it had negotiated long ago with the ILA, had failed to consider P&H’s interests or shown either arbitrary or bad faith conduct.

Concerning the second issue, the Board found that the MEA’s decision not to pursue a grievance on behalf of P&H was not made arbitrarily or in bad faith. In reviewing the limited case law on section 34(6) complaints, the Board noted that where the facts of a section 34(6) complaint are similar to those that the Board normally sees in section 37 complaints, the Board has generally relied on its section 37 case law by analogy. In previous decisions dealing with case law on section 34(6) complaints, the Board has found that, like in section 37 complaints, an employer representative has the sole discretion to decide whether or not to pursue a grievance. The Board reiterated that it will not second-guess or sit in appeal of a union’s decision on referring grievances to arbitration, nor will it substitute its own opinion for the union’s on whether to refer a grievance to arbitration, so long as the decision was not made arbitrarily or in bad faith. Applying these notions to the facts of this case, the Board found that the MEA investigated the circumstances surrounding the accident and chose a course of action which it considered appropriate in the circumstances. There was no evidence of ill-will, hostility, dishonesty or personal animosity such that bad faith conduct could be found.

Regarding the third issue, the Board found that P&H had not met its burden of proving that the 2:40 Practice was discriminatory because it only applied to employers engaged in grain handling. P&H argued that a practice can still be discriminatory if it does not treat all members equally for reasons that are arbitrary or unreasonable. However, the Board concluded that P&H failed to explain how applying the 2:40 Practice was illegal, arbitrary or unreasonable. The Board concluded that the 2:40 Practice was based on a rationale that effectively balanced the interests of the bargaining unit employees with those of member employers in the grain industry. As such, the MEA’s decision to agree to the application of the 2:40 Practice was not unreasonable as it allowed for this balancing.

With respect to the fourth issue, the Board found that the MEA’s investigation was not arbitrary. The Board pointed out that, in assessing a section 37 complaint, it does not assess or make findings pertaining to the merits of an employee’s grievance. The Board may, however, “review the facts of a grievance in order to understand whether the union’s investigation reflected the worthiness and seriousness of an employee’s case” (see McRaeJackson, 2004 CIRB 290). In this case, the Board could not find any conduct on the part of the MEA that would suggest its investigation was only perfunctory, cursory or superficial.

Finally, with regard to the last issue concerning bad faith conduct in the most recent round of collective bargaining, the Board found that the MEA had not engaged in bad faith conduct. In section 37 complaints, the Board has long held that in the context of collective bargaining, a union’s decisions are owed deference. The Board saw no reason to deviate from this approach of assessing the process involved in collective bargaining in the context of a section 34(6) complaint. Based on the pleadings provided by the parties, the Board was unable to find any evidence of hostility, animosity and/or bad faith on the part of the MEA toward P&H in the recent round of collective bargaining, which had resulted in a new collective agreement.

Federal Court of Appeal

Certification Application

Canadian Airport Workers Union v. International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers and Garda Security Screening Inc., 2019 FCA 263

The Federal Court of Appeal (FCA) confirmed the Board’s long-standing policies regarding membership evidence and displacement applications. The FCA dismissed an application for judicial review filed by the Canadian Airport Workers Union (CAWU) with respect to the Board’s decision in Garda Security Screening Inc., 2018 CIRB 878. In this decision, the Board dismissed the CAWU’s displacement application on the basis that the membership evidence was unreliable and that, in any event, the membership evidence did not demonstrate that the CAWU had the majority support required to obtain a representation vote. In that case, the Board followed its long-standing policy of delegating its investigation powers to its industrial relations officers (IROs) and have them report back by way of confidential reports.

On judicial review, the CAWU’s main argument was that the Board had denied it procedural fairness when it had decided its displacement application on the basis of the IROs’ confidential reports without disclosing these reports to the parties. These reports contained the results of the IROs’ investigation into the membership evidence and, in this case, confirmed significant irregularities in the membership evidence filed by the CAWU in support of its application. The Board had declined to disclose these reports to the parties in order to protect the confidentiality of the employees’ wishes in accordance with section 35 of the Canada Industrial Relations Board Regulations, 2012.

Ultimately, the FCA found that the CAWU’s right to procedural fairness had not been breached by the non-disclosure of the reports. It recognized that the CAWU’s right to know the case it had to meet, and its ability to respond, may have been constrained by labour law considerations, including the need to protect the confidentiality of employee wishes. However, these constraints were well known and had been endorsed by the courts for many years. The FCA further noted that although the CAWU was unable to address specific cases of irregularities, it knew—or should have known—the issues that the IROs were investigating, since the certified bargaining agent had raised these issues in its reply to the CAWU’s displacement application. Consequently, nothing had prevented the CAWU from presenting evidence to the Board supporting its position in that regard.

The FCA also upheld the Board’s long-standing policy to only order a representation vote in a displacement application if the applicant union can demonstrate that it has the support of a majority of members in the bargaining unit through accurate and reliable membership evidence, which the CAWU had been unable to do in this case. The rationale behind this policy is to preserve industrial peace by ensuring that employees are serious about changing bargaining agents and that they have expressed their sincerity by joining the union seeking to take over the bargaining rights.

Judicial Review of Board’s Decisions Post-Vavilov

Canadian Helicopters Limited (d.b.a. Canadian Helicopters Offshore) v. OPEIU, 2020 FCA 37

The Federal Court of Appeal (FCA) dismissed the application for judicial review, with costs, having found that the Board’s decision was not unreasonable. It applied the revised standard of review framework and guidelines set out in the judgments of the Supreme Court of Canada (SCC) in Canada (Minister of Citizenship and Immigration) v. Vavilov, 2019 SCC 65 (Vavilov); and Canada Post Corp. v. Canadian Union of Postal Workers, 2019 SCC 67.

Canadian Helicopters Limited (CHL or the employer) applied for judicial review of the Board’s decision in Canadian Helicopters Limited doing business as Canadian Helicopters Offshore, 2018 CIRB 891 (RD 891), in which the Board had granted the section 24(4) complaint filed by the Office and Professional Employees International Union (the union). The complaint alleged that the employer had breached the statutory freeze provision in section 24(4) of the Canada Labour Code. After the certification application was filed, CHL hired temporary pilots to fulfill its requirements under a short-term supply contract with British Petroleum on a different work schedule and overtime pay rate than those of the existing pilots. The complaint raised the question of whether the employer’s decision to hire temporary pilots on different terms and conditions amounted to “business as before,” particularly as CHL argued that it had engaged in costing and recruitment efforts prior to the certification application.

Because of the SCC’s decision in Vavilov, the FCA invited and received written submissions from the parties addressing the impact of the revised standard of review framework. CHL argued that neither the outcome nor the Board’s reasoning process were reasonable. CHL contended that the evidence established that it had engaged in planning for the hiring of temporary pilots well before the date of the certification application. It also argued that the outcome of RD 891 was not in keeping with authorities confirming that freeze provisions do not prevent employers from attempting to adapt to changing circumstances.

The union considered that CHL’s position amounted merely to a disagreement with the Board’s factual findings and that deference is owed to findings of fact. The union argued that the Board’s reasoning was unassailable: it had found no evidence that the different terms and conditions constituted a continuation of business based on what was in effect before the certification application was filed. As such, it had properly found that the change was inconsistent with “business as before” and had resulted in a breach of the statutory freeze.

The FCA agreed that the Board’s factual findings were dispositive in this case, as they led directly to the conclusion that the disputed changes went beyond “business as before.” Based on the record before the Board, the FCA did not find the conclusion unreasonable. Given CHL’s choice not to provide direct evidence of the costing model that it had adopted or what had been communicated to prospective hires during the recruitment process, the FCA considered that it had no basis for interfering with the Board’s decision not to draw inferences on the record before it that were more supportive of the employer’s position.

In this regard, the FCA emphasized the statement in Vavilov that reviewing courts must refrain from reweighing and reassessing the evidence considered by the decision-maker.

The FCA noted that it did not consider a possible argument that it had raised in relation to the two-prong statutory freeze test set out in United Food and Commercial Workers, Local 503 v. Wal-Mart Canada Corp., 2014 SCC 45, as this had not been argued before the Board.